By Ibanga Isine

On West Africa’s road to extortion, it’s as if every traveler has a secret “Guilty” sign taped to their back, and the officers—bless their overzealous hearts—seem to think their job is less about protection and more about perfecting their shake-down skills.

PREFACE: In the first part of this report, we exposed the excessive number of checkpoints along one of West Africa’s busiest highways, which connects Nigeria, Benin Republic, Togo, and Ghana, highlighting acts of impunity and human rights violations committed by state agencies charged with maintaining law and order. In this second part, we delved deeper, uncovering how these agencies and their accomplices extort so much money from commercial buses traveling the route—where more than 45 buses convey hundreds of passengers every day.

Welcome to West Africa’s highway of extortion

Accra, Ghana – Mr. Abednego (not his real name) has worked with a major Nigerian transport company for close to two decades, plying the Lagos/Accra route. Before his present role, he worked for many transport companies in Nigeria on local routes keeping an excellent safety record. His outstanding performance in vehicle management and safety earned him a promotion to international routes in the early 2000s. Since joining his current employer, Mr. Abednego has regularly driven a 12-seater bus between Accra and Lagos, making the trip at least four times a week, barring leave or vehicle maintenance.

Mr. Abednego is one of the few drivers willing to speak out about the robbery by security agents along the international corridor linking Nigeria, Benin Republic, Togo, and Ghana. He believes the extortion affects not only the high fares paid by travelers but also the cost of goods and services and sub-regional integration.

“I’m speaking out because I am tired of the corruption on this road. My colleagues and even my manager won’t talk because they fear retaliation from the security agents,” said Mr. Abednego, who requested anonymity to avoid repercussions from both security agents and his employer.

You can also read: How Governor Umo Eno spent a whooping N18bn on “Happy Hour”

However, air travelers within the four West African countries experience little or no form of extortion at the airports. Due to the regional reciprocity policy of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the average air traveler from Nigeria to Ghana pays only a fixed fare and possibly extra charges for excess luggage. Passport stamping upon arrival is free. But the situation is different for motorists and travelers along the sub-regional route, especially those selling locally-made goods, who are forced to pay significant fees for passport stamping.

While it was easy for our correspondent to cross the borders of Benin Republic and Togo, we discovered that Ghanaians and other nationals faced rough treatment and extortion if they overstayed their Nigerian visas. The same also applied to Nigerians who overstayed their Ghana visas.

During the several trips taken by our correspondent, we observed that many passengers traveled with their passports and ECOWAS certificates. However, a significant number of others had no means of identification. Mostly West African nationals without identity cards were forced to pay higher fares. Drivers used the extra money to bribe immigration officers, allowing these passengers to cross international borders.

In 2022, when our correspondent started the investigation, he paid an average of N55, 000 from Lagos to Accra with either an ECOWAS certificate or passport, and 650Ghc (N65, 000) when traveling from Accra to Lagos.

For trips made without any form of identification, transport companies charged between N67,000 and N70,000 from Lagos to Accra, and between 750Ghc and 870Ghc (N75,000 – N87,000) from Accra to Lagos in 2022 and early 2023.

Passengers with passports or ECOWAS certificates currently pay N80, 000 to travel from Lagos to Accra, while those without any proof of identity pay approximately N90, 000. This investigation involved 12 trips between November 2022 and February 2024.

On the final trip our correspondent took without any form of identification, the manager at the Ghana office of the transport company charged an additional N8, 700. “You must pay an extra N8, 700 so we can use it to clear you on the road,” the manager explained. “Our vehicle could be delayed by Immigration officials, and they might even pull you out.”

Tiered billing system

Mr. Abednego, while detailing the convoluted fare calculations for passengers, revealed that bus companies have a tiered pricing system based on the type of identification a passenger has. “Those with passports or ECOWAS certificates pay the standard fare from Lagos to Accra and from Accra back to Lagos,” he explained. “However, passports or ECOWAS certificates that have never been stamped at any of the borders—what we call ‘virgin’ passports—are charged more.”

Our correspondent asked immigration officials at each country’s borders why they charge more for “virgin” passports and no receipts are issued. The majority of officers remained silent, but a few who spoke up said it was standard practice.

He went on to describe how immigration officials along the Lagos-Badagry-Seme Highway exploit travelers. “Any passenger without a passport or ECOWAS certificate must pay a flat fee of N1, 000 at designated checkpoints and at the border. This fee also applies to other identity documents like national ID cards, driver’s licenses, and voter registration cards,” he said.

Passengers with “virgin” passports or ECOWAS certificates—those never stamped along the route—are required to pay N1, 000 to Nigerian immigration officers. Those without any form of identification must pay N2, 000 each. Mr. Abednego noted that drivers handle these payments at two main immigration checkpoints, one in Agbara and another at the Seme border before entering Benin. No receipts are ever issued for these transactions.

However, once the vehicle leaves Nigeria, payments for virgin passports or lack of identification are only required at the border crossings of the three neighboring countries.

In a startling revelation, we found that clearing agents work in cohorts with security agents along the notorious West African corridor to extort drivers and passengers. The corridor, a critical route for cross-border transportation in the sub-region, has become a hotbed for these agents, who strategically work with the security agents to undermine the free movement of people and goods as guaranteed by the ECOWAS Treaty.

The ubiquitous agents, all male aged between 20 and 30, have established a pervasive presence at various border posts, creating an intricate web of influence. Commercial drivers crossing the borders of each country rely solely on them to facilitate smooth passage in exchange for undisclosed commissions.

Apart from the clearing agents, security personnel, particularly in Nigeria, enlist the services of shabbily-dressed and menacing-looking young men, commonly known as “Kelebe” – a term that encompasses both gangsters and cultists. This unholy alliance is primarily aimed at tackling motorists who are unwilling to pay bribes along the route from Badagry to the Seme border.

The “Kelebe” do not only custody the ill-gotten money from illegal tollgates to evade detection by anti-graft teams but also actively participate in operating the staggering 132 checkpoints along the Nigerian route.

The illegal partnership with the criminal elements raises serious concerns about the abuse of power and corruption within Nigeria’s security sector. It also undermines the very essence of the country’s law enforcement.

A confidential interview with a driver revealed the full extent of the exploitation occurring on Nigeria’s side of the highway. According to the source, when security operatives withdraw at night or go on break, the “Kelebe,” boys frequently take over the checkpoints, pocketing the bribes collected.

Almost every commercial driver operating the local route from Lagos to the Seme border has experienced the brutality of these violent thugs. Those who attempt to pass the checkpoints without paying often get nail barricades hurled at the tyres of their vehicles, forcing them to stop and comply.

No record, no receipts, no evidence

During our investigation, we found that the exact number of commercial vehicles traveling the route remains unknown. However, through informal interviews with drivers and border officials, we discovered that approximately 30 small buses and 15 luxury buses, transporting over 800 passengers daily, are subjected to extortion on a daily basis. This does not include the locally operated transport service providers who move passengers between one border and another, as well as those traveling from Lagos to Seme and from Accra to Aflao.

A top official from Nigeria’s Department of State Services (DSS) told our correspondent in confidence that the agency lacks precise records of people and vehicles entering or leaving the country’s borders. Also, when we contacted immigration authorities in the four countries concerned, they were unable to provide data on the number of people and vehicles entering or leaving their borders.

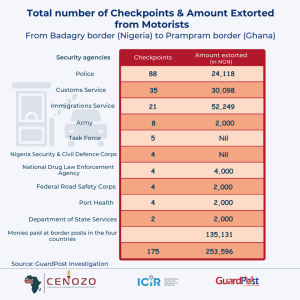

Our investigation revealed a stunning amount of money being extorted from commercial buses traveling between Lagos and Accra. Each 10-seater bus trip results in an estimated N253,596 in unlawful revenue. The rate becomes much higher for a 20-seater luxury bus, with over N507, 192 extorted for each trip.

When these data are broken down, the scope of the corruption becomes very glaring. Every day, no less than N15, 215, 760 million is extorted from transport operators and passengers along this route. This equates to N106. 5 million every week, N456, 472, 800 million per month, and a staggering N5. 4 billion per year.

Shockingly, this ordeal is not limited to big transport firms; minivans and sedans plying the route are also targeted, although what is extorted and their exact numbers are unknown. Unfortunately, the funds that are extorted along the route do not benefit the governments of the four West African nations. Instead, they line the pockets of corrupt security agents and their allies.

Checkpoints and amounts extorted by different security agencies

We generated the data in the tables below using insights gathered both formally and informally from credible sources along the route, as well as our reporter’s firsthand experiences.

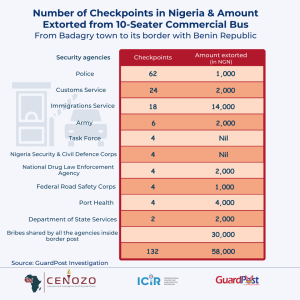

Nigeria

While Nigeria had the highest number of checkpoints along the route, it was not responsible for the highest amount of extortion. In fact, with over 62 checkpoints, the Nigeria police extorted only N1, 000.

Checkpoints and amount extorted by security operatives in Nigeria

Chart 1 shows the number of checkpoints from Nigeria’s Badagry town to the border with Benin Republic and the amount extorted from a 10-seater commercial bus going to Ghana

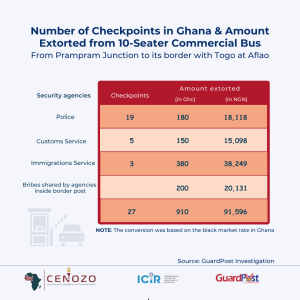

Ghana

Ghana came in second place, with 27 checkpoints stretching from Prampram Junction in Greater Accra to the border with Togo at Aflao.

Checkpoints and amount extorted in Ghana

Chart 2 displays the number of checkpoints from Prampram Junction in Greater Accra to Aflao, Ghana’s border with Togo and the amount extorted from a 10-seater commercial bus entering the country from Nigeria. The conversion was based on the black market rate in Ghana.

Benin

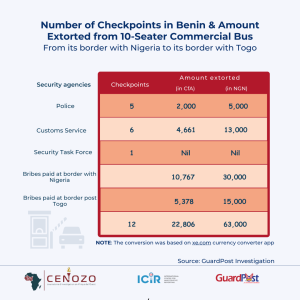

Benin Republic has about 12 checkpoints created by three law enforcement agencies along a distance of approximately 163 kilometers or three hours and thirty minutes of driving time from its border with Nigeria to its border with Togo.

Chat 3 shows the number of checkpoints from Benin Republic’s border with Nigeria to its border with Togo and the amount extorted from a 10-seater commercial bus passing through the country. The conversion was based on xe.com currency converter app.

Togo

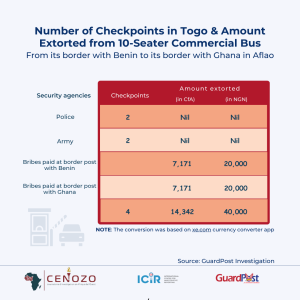

The Republic of Togo, which has the best-maintained highway along the route, has only four checkpoints, the least number of the four countries.

Chart 4 shows the number of checkpoints from Togo’s border with Benin Republic to its border with Ghana in Aflao and the amount extorted from a 10-seater commercial bus passing through the country. The conversion was based on xe.com currency converter app.

Total number of checkpoints and amount extorted along the route

Chart 5 shows the total number of checkpoints and amount extorted from motorists from Nigeria’s border city of Badagry to Prampram, a town on the outskirts of Greater Accra, Ghana.